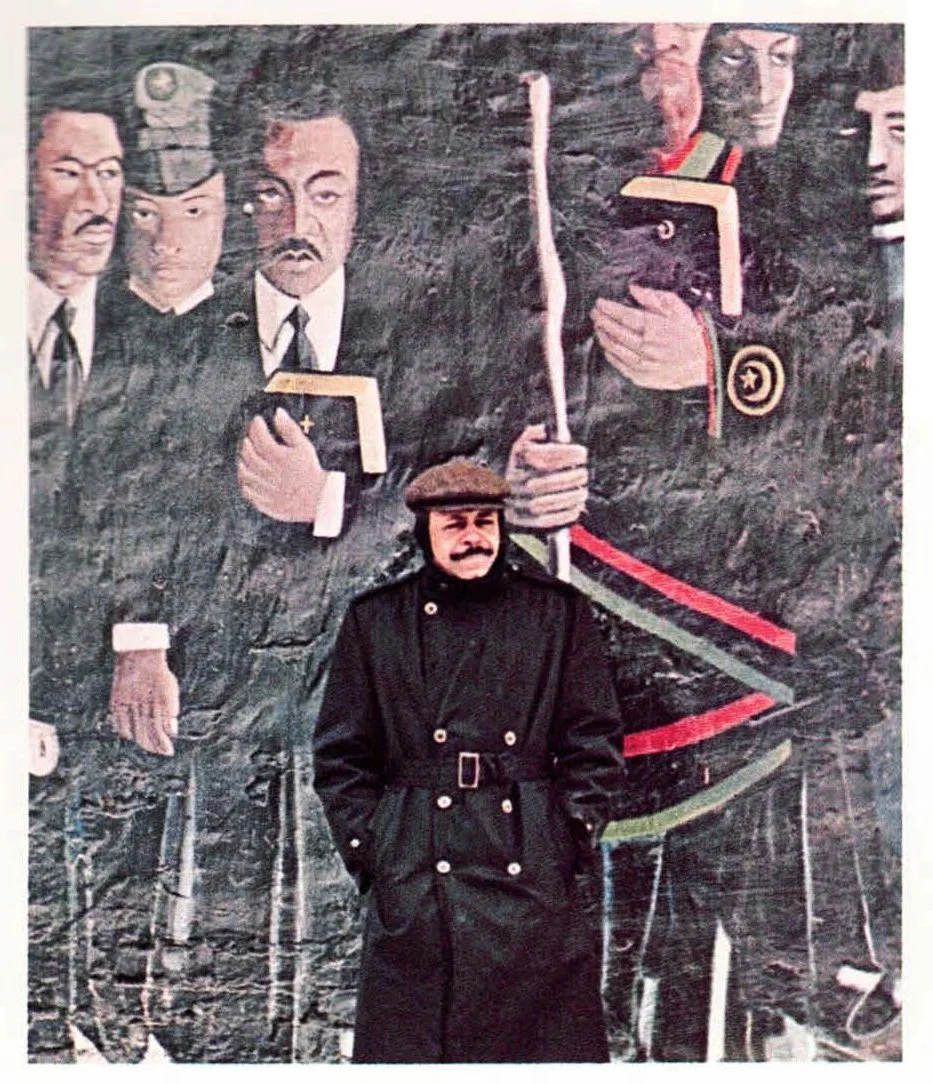

William “Bill”

Walker

(1927-2011)

untitled

1976

marker on tan paper

24 x 17 inches

signed and dated

In August of 1967, on the southeast corner of 43rd and Langley Streets, Chicago, Illinois, a group of African American artists came together to paint the landmark mural that sparked a people’s art movement. William “Bill” Walker was instrumental in the creation of the Wall of Respect. The purpose of the project was to “honor our Black heroes and to beautify our community.” It soon became, in the words of fellow artist Jeff Donaldson,

An instantaneous shrine to Black creativity, a rallying point for revolutionary rhetoric and calls

to action, and a national symbol of the heroic Black struggle for liberation in America.Cities across America followed suit with murals of their own. Bill Walker continued to paint murals in the city of Chicago, as he had painted them before 1967, solidifying his role as father of the community mural movement - capturing the “human side of street life in the city.”

Bill Walker was born in 1927 in Birmingham, Alabama. An only child, he was initially raised by his grandmother in a desperately poor ghetto of “bleak little shacks” with outhouses known as Alley B. In 1938, he was sent north to Chicago to join his mother who worked as a seamstress and hairdresser. They lived in a variety of places in the Washington Park area and he eventually attended Englewood High School.

Walker was drafted in WWII and re-enlisted to receive college tuition under the GI Bill. He was a mail clerk, then an MP with the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the all black command under which the Tuskegee Airmen fought. In 1947, he painted his first murals while in the military. While stationed in Columbus, Ohio he became friends with Samella Lewis. He often stayed with her family and assisted her on a few commissions.

In 1949 he enrolled in the Columbus Gallery School of Arts. He began studying commercial art and later switched to a concentration in fine art. Walker won the school’s 47th Annual Group Exhibition “Best of Show” award in 1952. He was the first African-American to do so. Walker credits Joseph Canzani with encouraging his interest in mural painting. At school he studied the early Renaissance fresco painters. It wasn’t until after his graduation that he learned about the Mexican muralists - Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, and Jose Clemente Orozco. He was particularly impressed with the way they incorporated structural elements into their compositions. Walker also cited Jacob Lawrence, Charles White, and William McBride as important influences.

After graduation, Walker headed to Nashville and Memphis where he painted murals for a Baptist church, a local Elks club, and the Flamingo Club, a nightclub near Beale Street. While researching and preparing to complete another mural of a plantation scene, he had an important epiphany. He realized he needed to create art that spoke for those who had been marginalized. Walker returned to Chicago and worked as a decorative painter for a variety of north-side interior designer firms.

“The artist-to-people communication is the kind of relationship that would place the artist and his work in a position of respect, pride, and dignity—all of which he should have. These views are not based on the feelings of an idealist hoping for something that cannot be or believing in something he has never experienced. They are founded on the grounds of experience. Experience of talking with people in a community during the time that the art project is in progress; of discussing the conditions of their problems and the world and trying to realize how art can become more relevant to the people of the world.”

By the mid-1960s, Walker was formulating an idea for a mural in the area near 43rd and Langley, which never came to fruition. However, in May of 1967, the Organization of Black American Culture was formed and the opportunity again arose. OBAC was cofounded by artist Jeff Donaldson, sociologist Gerald McWorter, and Hoyt Fuller, editor of Negro Digest, and was dedicated to visual art, music, writing, dance, and theater. Walker floated the idea of a mural at the location. The group couldn’t just simply paint a mural and leave it at that.

Walker knew the neighborhood well and secured permission from business owners, community leaders, and street gangs. The residents were a big part of the process as well. Jeff Donaldson and Eliot Hunter, Wadsworth Jarrell, Barbara Hogu-Jones, Caroline Lawrence, Norman Parish, Edward Christmas, Myrna Weaver, and many others contributed sections to the wall. Walker was responsible for the section on religious leaders. Walker had originally painted the portraits of Black Muslim leader Elijah Muhammad, Nat Turner, and Wyatt Walker, a New York minister and civil rights activist, but when threatened with a lawsuit by Muhammad, who did not want to be pictured on the same wall as Malcolm X, he erased the section and replaced it with a composition of Nat Turner.

The members of the OBAC eventually drifted apart- some, Donaldson, Jarrell, Jones, and Lawrence formed AfriCobra, and Walker, who remained in the neighborhood, came to be the “guardian of the wall.” As a result of the impact the Wall of Respect had in Chicago, similar walls were created in cities across the country. Walker worked on the Wall of Dignity in Detroit and the Wall of Truth, which was located across the street from the Wall of Respect. He co-founded the Chicago Mural Group (now known as the Chicago Public Art Group) with John Pitman Weber and Eugene Eda and completed more than 30 murals over the next four decades in working-class Chicago neighborhoods. In 1975, he formed his own mural group known as International Walls, Inc.

Walker turned increasingly to studio art in the late 70’s. Chicago State University held the exhibition, Images of Conscience: The Art of Bill Walker in 1984. The exhibit consisted of 44 paintings and drawings in three series: For Blacks Only; Red, White, and Blue, I Love You; and Reaganomics. The show was not without controversy as the images presented were not pretty, but dark representations of urban black neighborhoods. The exhibition traveled to the Vaughn Cultural Center, St. Louis and the Paul Robeson Cultural Center, Pennsylvania State University. Most recently, Walker’s work was presented in the exhibition Bill Walker: Urban Griot, held at the Hyde Park Art Center, November 2017 - April 2018.

Childhood is Without Prejudice, 1977; enamel on concrete, acrylic restoration, 8’ x 35’, Fifty-Sixth Street Metra Station underpass, 56th St. and Stony Island Avenue, Hyde Park, Chicago, IL. Photo: Chicago Public Art Group

Selected Exhibitions

Chicago Artists Exhibition; Art Institute of Chicago, IL, 1958

AFRICOBRA II; Studio Museum in Harlem, NY, 1971

Samuel Crockett & Bill Walker; South Side Community Art Center, Chicago, IL, 1977

Images of Conscience: The Art of Bill Walker; Chicago State University, IL, 1984

Since the Harlem Renaissance: 50 Years of African American Art; Bucknell University, PA, 1984

The People’s Art: Black Murals, 1967-1978; Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, Philadelphia, PA, 1986

Black Power, Black Art...and the Struggle Continues: Political Imagery from the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s; San Francisco State University, CA, 1994

Visual Politics: The Art of Engagement; San Jose Museum of Art, CA, 2006

Art & Politics in Chicago; DePaul University, Chicago, IL, 2008

Place of Validation: Art & Progression; California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA, 2012

Public Murals

Wall of Respect, 1967

All of Mankind; 617 W. Evergreen Ave., Chicago, IL; Murals celebrating the martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War; 1973

The History of the Packinghouse Worker; 4859 S. Wabash Ave., Chicago, IL; Depicts the history of the Amalgamated Meatcutters and Butchers Workmen Union. It was one of the first Chicago public murals dealing with labor and worker’s Unions; 1974

Childhood is Without Prejudice; . 58th St. and Stony Island Ave., Chicago, IL; Mural celebrating the role of the nearby Harte School in promoting racial harmony; 1977