James

VanDerZee

(1886-1983)

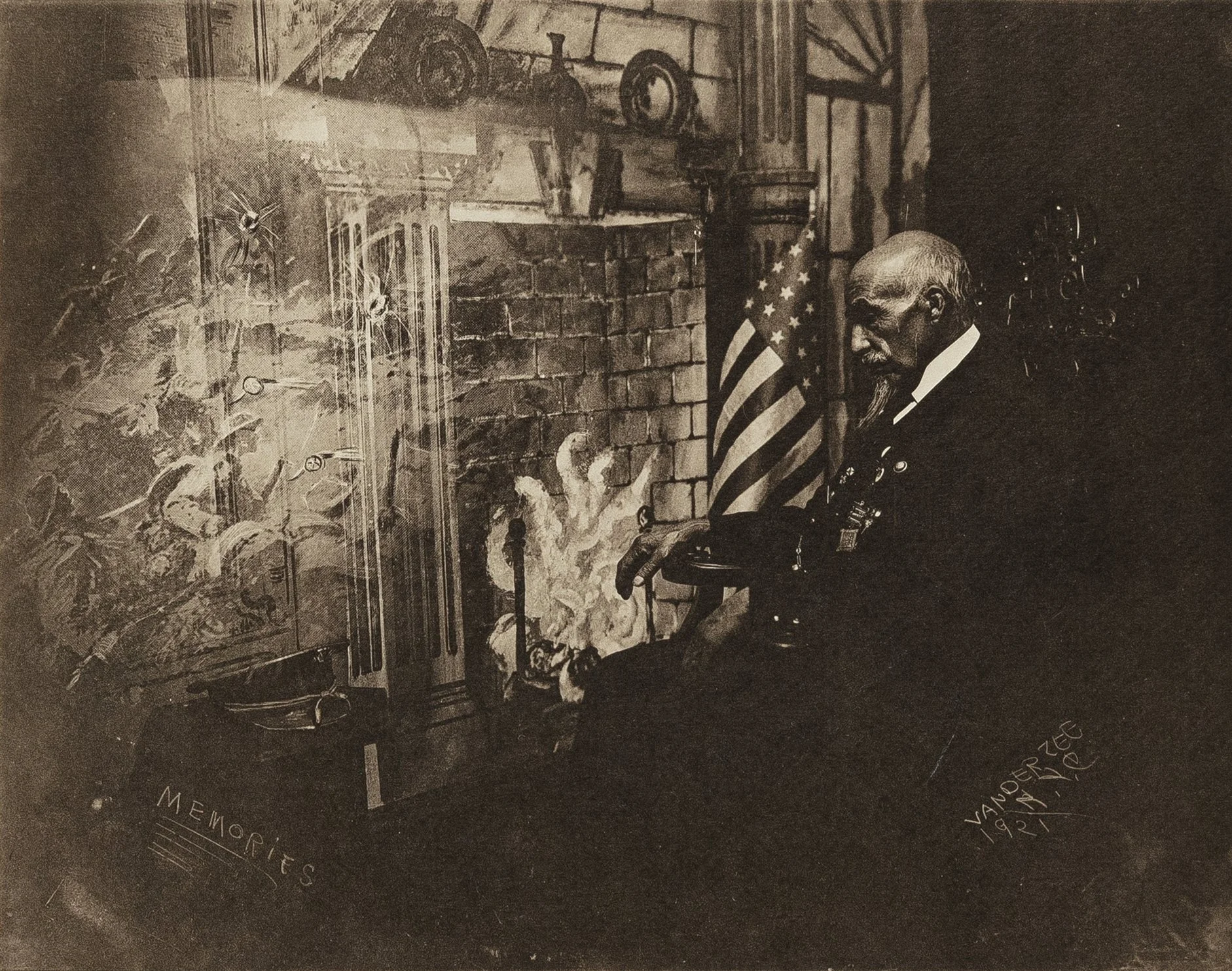

Memories

1921

photogravure

9 x 11-1/2 inches (image), full margins

signed, titled and dated in plate only

James VanDerZee was one of the most celebrated photographers of the Harlem Renaissance, best known for his elegant and carefully staged portraits that documented Black life in the early to mid-20th century. Born in Lenox, Massachusetts, VanDerZee demonstrated a talent for music and photography at an early age before moving to New York City, where he would establish his lifelong career.

In 1917, VanDerZee and his second wife, Gaynella Greenlee, launched the Gaynella Greenlee Guarantee Photo Studio in Harlem, called G.G.G. Studio, at "109 135th Street, sandwiched between a branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture) and the headquarters of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA)." (1) At a time when photography was often used to reinforce stereotypes, VanDerZee’s portraits projected dignity, refinement, and aspiration. His sitters ranged from families, church groups, and civic organizations to cultural icons such as Marcus Garvey, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Adam Clayton Powell, and Joe Louis. They were often posed with elaborate props and backdrops that suggested prosperity and respectability. His images became a visual record of Harlem’s social fabric during its cultural flowering.

In addition to studio portraiture, VanDerZee documented parades, fraternal organizations, weddings, and funerals, producing a vast archive of African American life in the 1920s and 1930s. His work for Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in particular captured a pivotal chapter in Black political and cultural history.

VanDerZee’s career declined after World War II due to the increase in sales of cameras aimed at the amateur consumer. However, he was rediscovered in 1969 through the landmark exhibition "Harlem on My Mind" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which brought his work to national prominence.

It has been said that the successful recipe for a Van Derzee image was equal part authentic pride of the sitter and equalpart carefully constructed artifice, courtesy of the photographer. Using painted backdrops, careful lighting, and deft retouching, he crafted portraits that radiate ceremony, aspiration, and style. These images were prized by families, social clubs, and celebrities alike. Today, they are prized for their intimate look at life in Harlem in the early 20th century.

https://www.moma.org/artists/6074-james-van-der-zee

Self Portrait, (public domain)

Selected Exhibitions

Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1969

Lenox Library, Massachusetts, 1970

Studio Museum in Harlem, NY, 1971

Lunn Gallery/Graphics International, Washington, D.C., 1974

The Legacy of James Van Der Zee: A Portrait of Black Americans, Alternative Center for International Arts, NY and Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, 1979

Retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C., and Howard Greenberg Gallery, NY, 1994

James VanDerZee: Eighteen Photographs, Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska, 2015

James Van Der Zee’s Photographs: A Portrait of Harlem, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2021-22

New York City, 1920s, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2020-23

untitled

1924

photogravure

12 x 8 Inches (image), full margins

signed and dated in plate only

“This studio portrait shows a man dressed in modern attire, but clad in shackles from neck to feet. The man is most likely a magician or escape artist like Harry Houdini or Black Herman, both popular performers when this photograph was taken. But the sight of a black man in chains standing in the splendor of African American photographer James Van Der Zee’s studio creates an image that is more complicated than a standard promotional photo. VanDerZee was one of the most successful photographers in Harlem, in part because he shared the racial pride of his sitters and always strove to create elegant, yet idealized portraits. He documented everything and everyone in the neighborhood, from the emerging black middle class to celebrities of the Harlem Renaissance, from community gatherings and weddings to funerals.”