The Rich Tapestry of

Black Artistic Expression

in the James T. Parker Collection

by Chenoa Baker, independent arts writer and curator

Figurative work has always been important in the African American canon; in particular, many were both a political and visual response to the proliferation of minstrel representations and a means to represent the Black ordinary, once W.E.B. Du Bois and others ensured that Black art was saturated with socio-political subject matter to advance the race. In the James T. Parker Collection, there are many figurative works, especially expressive faces that convey complex messages and themes, as well as demonstrate an artist’s range. In the political arena, some examples from the James T. Parker Collection include: Paintings I Promised Never to Paint: Man Crying by Robert Colescott (1965), Confrontation by Elizabeth Catlett (1941), American Gothic (1942) by Gordon Parks, and Everything Will Be Alright (2004) by Kerry James Marshall.

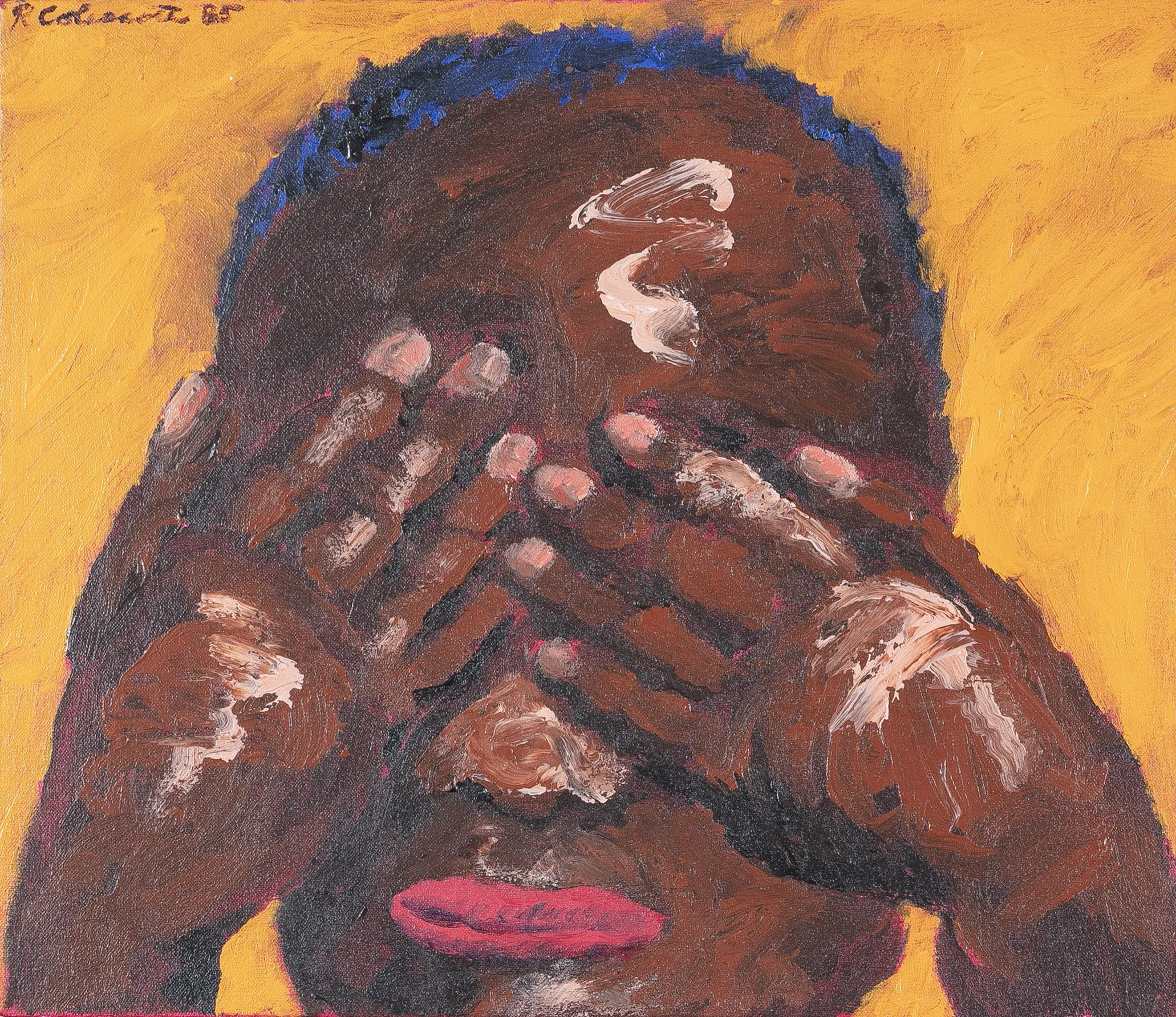

Paintings I Promised Never to Paint: Man Crying, 1965

Confrontation, 1941

American Gothic, 1942

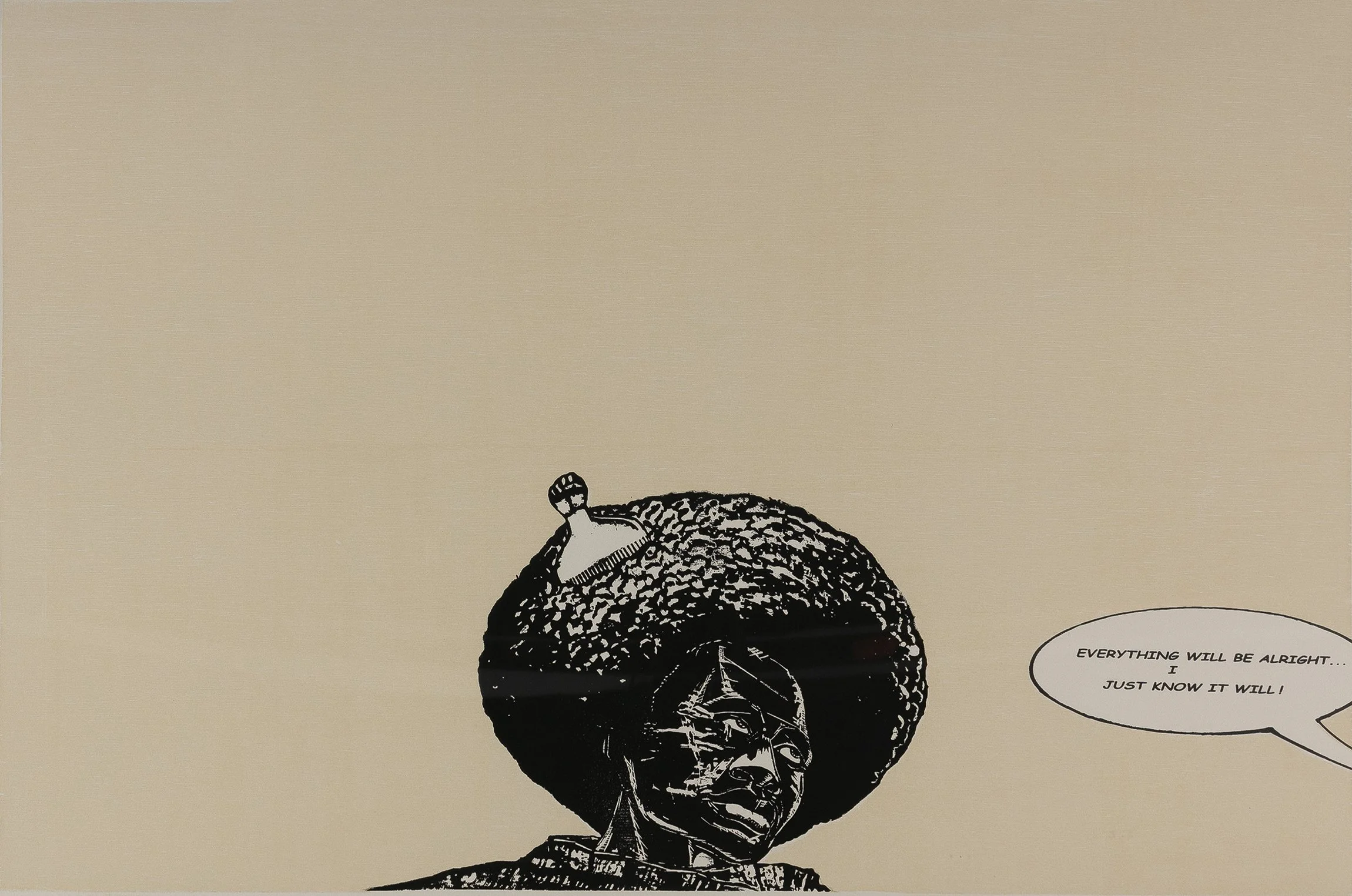

Everything Will Be Alright..., 2004

Colescott depicts a man shielding his eyes, the most expressive facial feature, with his hands. The work is in his typical oil painting style, characterized by loose brushstrokes that blend colors almost pastel-like. However, it conveys a simplicity rarely seen in his work, as he is mostly known for crowded compositions. His style has been described as:

“marrying a cartoonish style—reminiscent of that of his contemporary R. Crumb, the Bay Area satirist—with rough textures and strong colors, Colescott initially draws the viewer into what appears to be a humorous, exuberant world, but beneath the surface, there lies a harsh, arresting commentary on contemporary race relations.” (1)

This difference strips back the layers to focus on the raw emotion of the flat-line mouth and the concealed entryway to the soul.

Even as the title suggests, for Colescott, the subject matter is beyond a personal line of what he typically wanted to represent, yet he painted it anyway. Did he do it to show the vulnerability and fragility of Black men that aren’t often seen in the canon? It is as if he felt the need to humanize them. But why was it out of his repertoire ordinarily—was it because the image of a strong Black man was so needed when society constantly berated Black men, requiring constant affirmation? Perhaps the viewer may never know. However, what is clear is that the shielding of the eyes acts as a deliberate protection within this vulnerability.

(1) Sims Lowery S. and Dennis Carr. CommonWealth: Art by African Americans in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2015, “Men,” 64.

Catlett, on the other hand, offers a different type of aggression and protection in the cropped scene of Confrontation. Without context, the viewer sees a white woman with blonde cropped hair, large slits for eyes that make her almost mask-like, and scrunching her face in rage with an open mouth toward a Black woman, whose three-quarter face is visible with her back to the viewer. The Black woman retains a calm, solemn expression. Turning her face fully away from the viewer protects her full range of emotion, and keeping a calm face during this conflict is an act of self-preservation. This image may be the first rendering of a Karen (2), diametrically opposing the white woman and the Black woman here. It can be read as the Black woman having a sense of soft power as resistance. As there is no context to this scene, which is photographic in its cropping despite being a painting, it becomes not a specific incident but a universalized conflict. It also echoes the sentiment of the artist and her encounters. While this predates Catlett’s involvement in the Black Arts Movement and the rise of McCarthyism in the US, Catlett gave a speech in 1961 called “The Negro People and American Art at Mid-Century” (3), which became the movement’s manifesto. Therein, “she urged artists of color to spurn the inherently racist and exclusionary network of American museums and galleries and to organize their own all-[B]lack exhibits. She also issued a directive to Black artists to create art that would ‘express… racial identity, communicate with the Black community, and participate in struggles for social, political, and economic equality.’”(4) This speech launched artists into ideas of culturally-informed self-naming, rejection of white institutions (which differed from the Harlem Renaissance), and the development of an Agitprop style. Undoubtedly, the seeds for these thoughts were sown in the War era.

(2) For more about the dissection of Karens, check out my zine “The Horror of Karen” which may provide added richness to the context of Elizabeth Catlett’s work.

(3) Farrington, Lisa. African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History, Oxford University Press: 2016, 246.

(4) ibid

1941; oil on canvas

15 x 18 inches

signed and dated

Exhibited: MacAlester College, St Paul, MN., 2001

Park’s American Gothic is a political commentary through the use of appropriation (a very effective method in pushing a political message). During World War II, Parks visited Washington, DC, on a Rosenwald Fellowship and met Ella Watson, who cleaned the Farm Security Administration offices. (5) Once he had her pose, the satirical commentary revealed itself: eureka, American Gothic. Parks’ trained eye saw the famed American Regionalist work by Grant Wood, created in 1930. The original painting echoed traditional values and positioned the two figures, one holding a pitchfork (which Parks replaced with an upturned mop and broom), as pillars of American society. With Parks’ reinterpretation, Watson and those Black domestic laborers whom she represented were important fixtures in keeping America going. It is as if to say that folks like her are the backbone. Not only did the American flag in the background do this work, but the naming and the way she holds the mop also reinforce the message. Her cleaning government buildings while the government was at war abroad placed a stinging irony on not taking care of and discriminating against the Black workforce at home. Watson’s face looks matter-of-fact, somber, and gazes beyond the camera as if she’s simply enduring another workday. Therefore, this became one of the most important photographs of the 20th century.

(5) “American Gothic: Gordon Parks and Ella Watson,” Gordon Parks Foundation, n.d. https://www.gordonparksfoundation.org/publications/gordon-parks/american-gothic-gordon-parks-and-ella-watson#:~:text=Created%20as%20part%20of%20an%20extensive%20collaboration%20between,a%20flag%2C%20a%20woman%2C%20a%20broom%2C%20a%20mop.

1942; (later imp.)

silver print

9-1/3 x 6-3/4 inches

signed

Another political work that came much later is Kerry James Marshall’s Everything Will Be Alright. It depicts a Black figure against a plain background, evoking a newspaper-like duotone. The newspaper-like feel and 1970s aesthetic draw upon the work of Emory Douglas, the artist and newspaper creator of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. However, the figure has Marshall’s signature onyx-black-tone skin. Showing the figure in ‘pure black’ is in itself a political statement, centering darkness and blackness. The figure is in the bottom quadrant of the print with a rounded afro, an afro pick set in the hair with a fist at the end—emblematic of Black Power. The figure is cut off at the shoulders, and its angular face looks off into the distance. A speech bubble, emerging from somewhere beyond the work, says,

“Everything will be alright, I just know it will!”

2004; woodcut and screen print on grey BFK Rives paper

27 x 41-1/2 inches (image)

30 x 44 inches (sheet)

signed, dated, titled and numbered, 2/25

Gamin (1929) by Augusta Savage sits somewhere between the political and the mundane. Savage worked during the Harlem Renaissance; some might argue she was one of the chief architects of the movement, which actively proliferated portrayals of Black people that were positive to counteract the lascivious nature of minstrel stereotypes. The name comes from the French term etched onto the bottom of the sculpture, which means “streetwise” in French. (6) It depicts the artist’s nephew in a newsboy hat, evidence of a working Black youth, decidedly urban yet productive. His eyes, caught in medias res, are in the direction of his head, cocked to the side slightly, radiating effervescent cool.

(6) “Gamin,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, n.d. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/gamin-21658

1929; pllaster with bronze painted patina

9 inches (h)

signed and titled

Additionally, the James T. Parker Collection showcases a plethora of works showing the full spectrum of interior life. Each artist has a different interpretation of rendering the head, often considered the place of dreams and ideation, and a profound power.

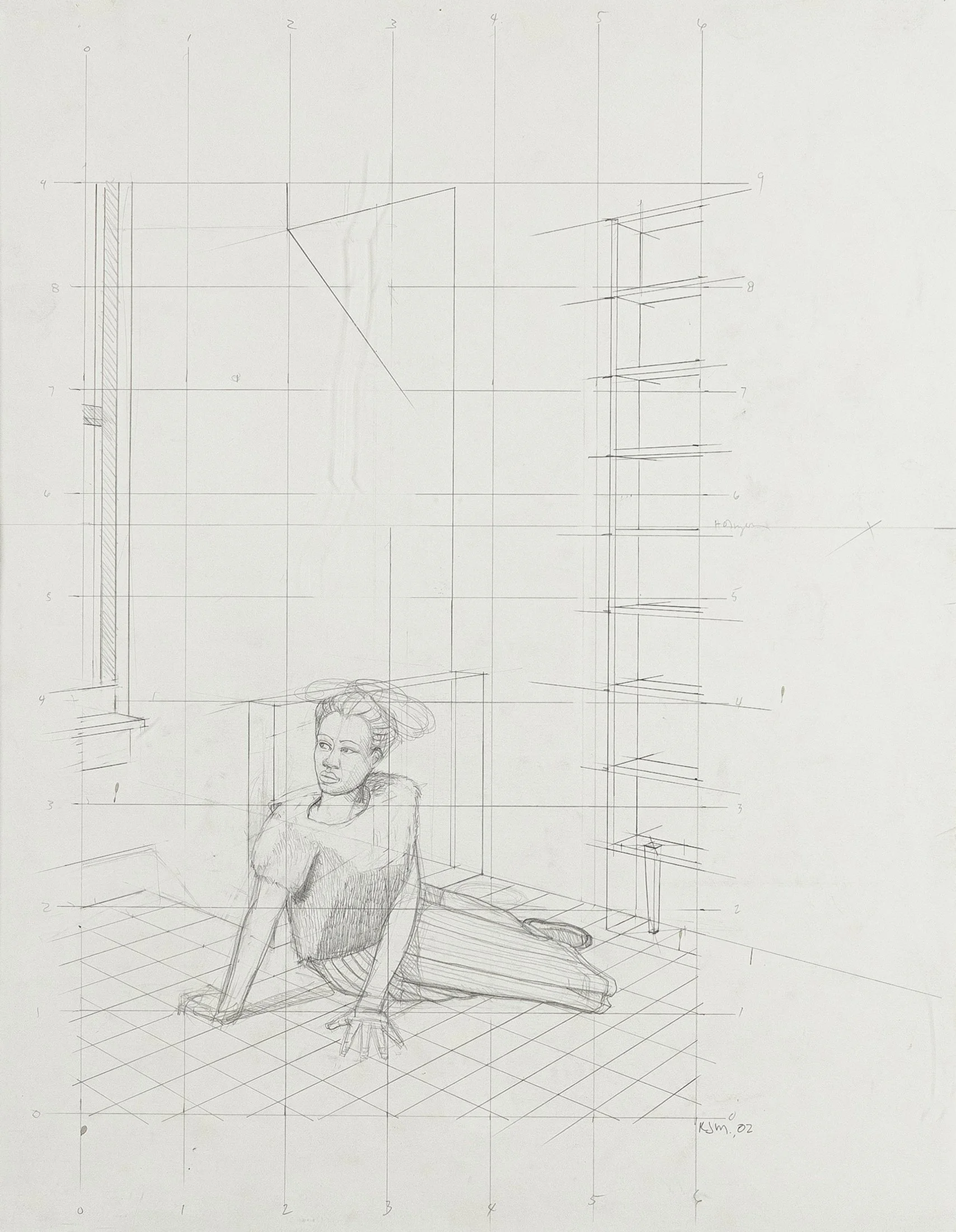

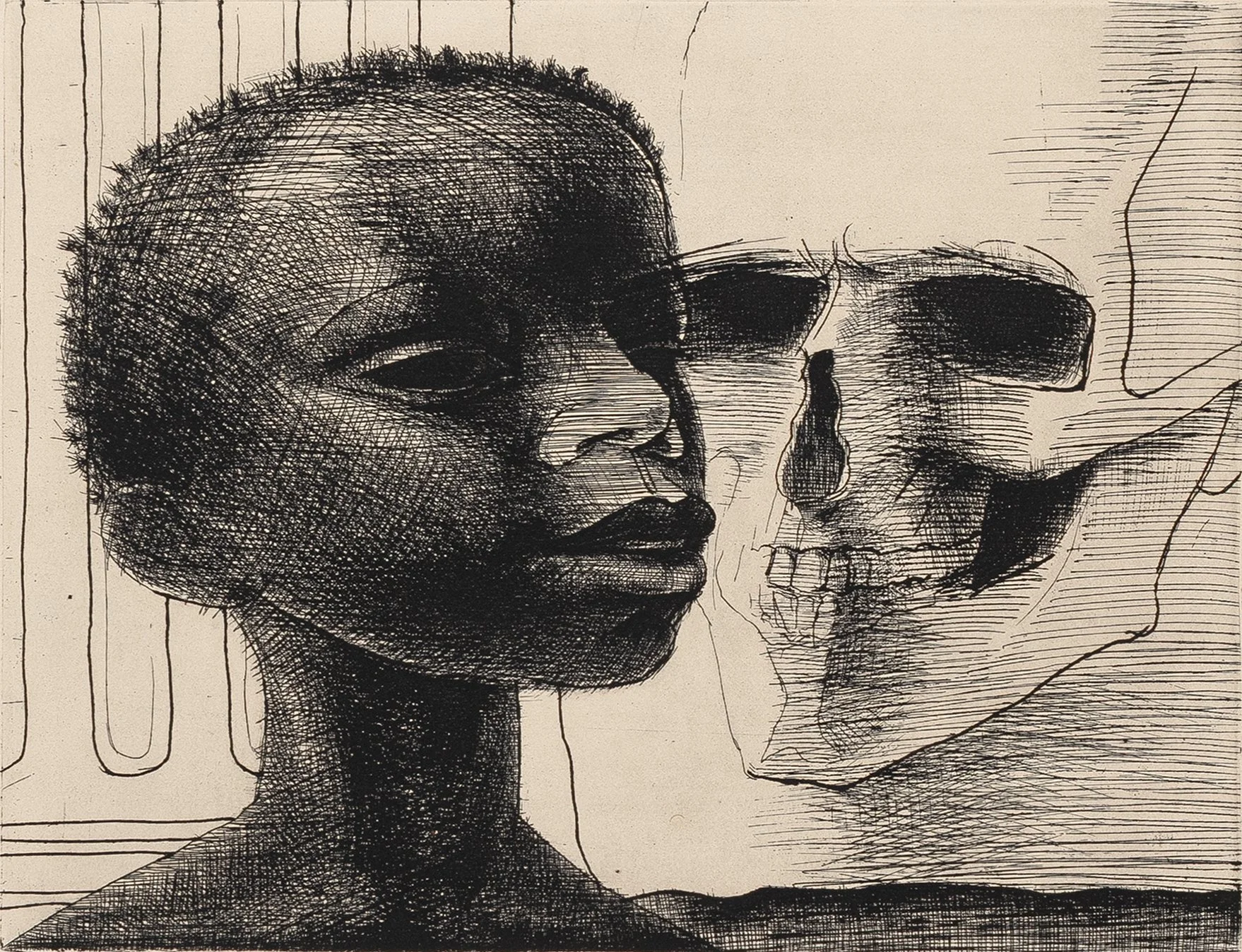

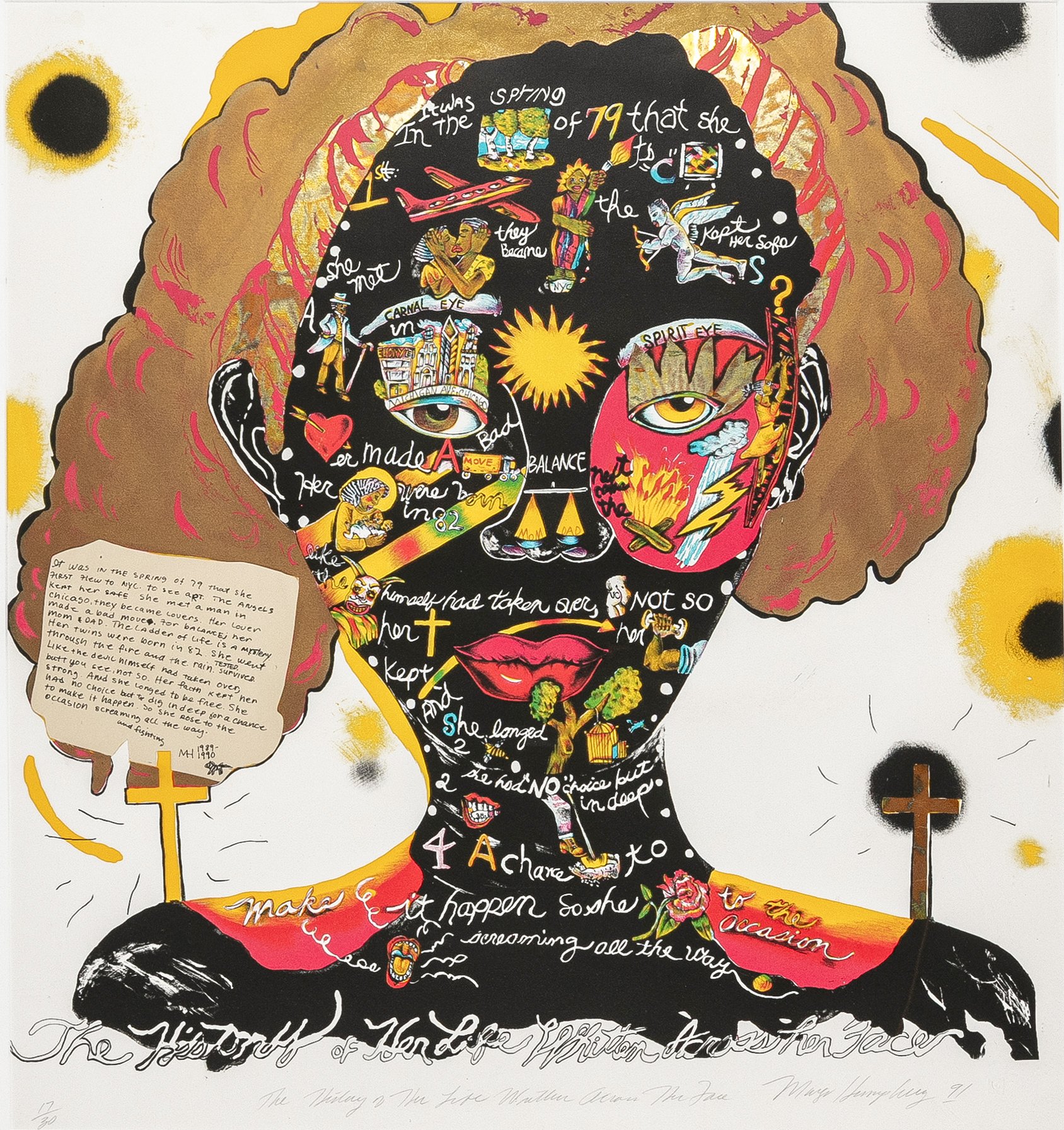

The following artists respond at different points in history to that body part: Compositional Study for SOB, SOB (2002) by Kerry James Marshall, Untitled, the artist’s wife (Eva Gillon) (1950) by Marion Perkins, Untitled, head (1950) by Marion Perkins, Untitled (1976) by William Walker, Dialogue (1973) by John Wilson, Power Object: Homage to Joseph Cornell (1991) by Renee Stout, and The History of Her Life Written Across Her Face (1991) by Margo Humphrey.

Marshall’s Compositional Study for SOB, SOB shows a rare glimpse into the artist’s process. It showcases a grid made from graphite where elements like the beginnings of a bookcase, window, and figure fit into the space. In the lower quadrant, much like his other work created two years later, Everything Will Be Alright, a woman reclines with her legs bent back and torso facing the viewer. The importance of her spatially fitting into the grid is that it ensures her limbs are not uncharacteristically foreshortened. Similar to the other work, this woman (styled contemporarily) looks off into the distance, demonstrating an intimate moment of contemplation.

The two works by Perkins are carved stone, often seen as the medium of permanence and importance from a personal and societal perspective. For example, the head of his wife was not the only one of his kind, as there is another record of a similar object in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. For the artist, he memorializes his wife by recreating her face, which has rounded features: arched eyebrows, oval-shaped eyes, prominent cheeks, and a rounded mouth with added carving framing the face to create her hair. The Untitled work is carved out of marble, which has Classical Greco-Roman and Egyptian connotations. Instead of this work having a name, it is as if he is creating his own relic, echoed in the exaggerated, elongated, and mask-like features. He also undoubtedly draws from the visual culture of heads that were prominent as ways of honoring ancestors in West Africa, especially among royals in Benin and nobles in the Akan Empires.

The head motif also spills over into other works of the collection, such as John Wilson’s Dialogue. He is most known for his large-scale bronze head, known to the people as ‘Big Head’ in Roxbury, MA, though its actual title is Eternal Presence. His inspirations for that work are pre-Colombian Olmec Heads, the visual language of Mexican muralists, and Buddha statues in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, all of which appear in the shape and mask-like eyes of Dialogue. (7) However, the example in Parker’s collection differs because it is a print that showcases a three-quarter turn of a face attached to a neck with a slightly parted mouth, cross-hatching creating the dark hue of the skin, and displayed next to a static and flattened skull. There is also a corrugated wall with moulding, suggesting that this work could be in a museum collection, depicting an individual looking away from the work as if a passerby. In conversation with one another, it brings the history of the first human being, an African, re-discovered around 1974 (i.e. Lucy), and the notion of phrenology skull comparison to determine ‘Africanized’ features to the surface. Phrenology brought so much harm to the Black community, as it’s often attributed to being used as justification for the oppression of Black people and eugenics, so how does this image hold its own and transcend those harmful structures? The secret is in the smile. The curious nature of the subject and looking beyond, while also being mask-like, ties them to something ancient and anatomical, reminding us that they are a living, breathing human being.

(7) “ John Wilson: Eternal Presence,” The Trustees of Reservations, n.d. https://thetrustees.org/content/eternal-presence/

Speaking of anatomical structure, Renee Stout’s work has a central head made from a found object at the top, with a structure of stacked cabinets, a bird, and a necklace of shells, feathers, and other materials wrapped around its neck. Stout dedicates this work to a white American assemblage artist, surrealist, autodidact, and naturalist, Joseph Cornell, yet she Africanizes the imagery through the dark wood and rusted head as well as the composition. While it is created with ‘modern’ materials, this bricolage harkens back to Congolese nkisi power figures, which are dressed in shells, medicinal bundles, feathers, and other materials, and activated with nails piercing the core. This visual reference imbues the work with a mystical power, but it also draws from the cabinet of curiosities with the jars of unidentified things collected and on display within the figure’s body.

Lastly, Margo Humphrey depicts a woman’s head by displaying what’s on the inside on the outside. This bust is characteristic of Humphrey’s Surrealist style with bold color and its reinterpretation of religious iconography. In this work, each eye is labeled ‘the carnal eye’ and ‘the spirit eye,’ with a sun between the eyes representing the ‘third eye.’ There are crosses, boats, lovers embracing and kissing, deviant/trickster figures, airplanes, a reinterpretation of the Statue of Liberty as a Black woman, a mother breastfeeding babies, a cupid figure, fire, trees, flexed muscles, an open mouth, lightning bolts, clouds, and flowers. These doodles are also accompanied by handwritten text that swirls and talks about the existential nature of daily life. At the bottom, it declares that this is

“The history of her life written on her face.”

There is also text on the face that talks about the good and the bad, balance, and a love story of the Spring of ‘79. It is also present in the note posted by the face without annotations and pictograms. The ebullient hair from gold leaf further makes this ordinary Black woman imbued with divinity. It completely embodies the divine feminine as well as the navigation of earthly trappings, especially in the two crosses, one on either side of the figure’s shoulders, representing all she has to carry in this life.

Taken together, the works in James T. Parker Collection reveal how Black artists across generations have continually returned to the head and face, not just as sites of likeness, but as powerful vessels of memory, identity, resistance, and self-determination. Whether through the shielded eyes of Colescott’s vulnerable figure, the steadfast calm of Catlett’s heroine, the quiet dignity of Parks’s Ella Watson, or the layered symbolism of Humphrey’s divine feminine, these portraits reject the flattening gaze of stereotype and reclaim the right to complexity. The spectrum spans the political and the intimate, the historical and the speculative, the monumental and the everyday. In this way, the collection becomes more than an archive of artworks—it is a living record of how Black artists have envisioned themselves and their communities, challenging the narratives imposed upon them and crafting new ones with conviction, care, and imagination.